Beginning to learn scales on the guitar and wondering what the difference is between major and minor scales, and more importantly, how to use them? In the following article, we’re going to explain how these two foundational scales differ technically, and also how you might use one as opposed to the other. If you don’t have time to read the full article below is a quick, albeit brief summary:

The difference between major and minor scales are the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes of the scale (aka scale degrees). For minor scales the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees are one semitone (1 fret on the guitar’s fretboard) lower in pitch than their major counterpart, giving the scale a darker, more melancholy sound when compared to the brighter, happier sounding major scale.

Building Major and minor scales

What is Major and Minor?

If you hear the term ‘quality’ referred to in music, more often than not rather than describing how good the piece of music is, we are referring to the character of a musical component (e.g. chord, scale, interval, or key) defined as Major or minor, and to a lesser extent augmented or diminished. We’ll focus on Major and minor scales for today but keep in mind there are four specific categories when defining the quality of a scale or musical element.

While Major and minor scales are capable of creating entirely different moods, they are perhaps more alike than different in structure.

For example, both Major and minor scales are diatonic scales, meaning they consist of 7 notes including 5 whole steps (2 frets apart on the guitar) and 2 half steps (1 fret apart).

The order of notes which governs where each whole and half step is placed within the scale is how major and minor scales are differentiated, resulting in (as explained above) the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes of the minor scale being a semitone lower than the major scale. Otherwise, the remaining four notes are exactly the same.

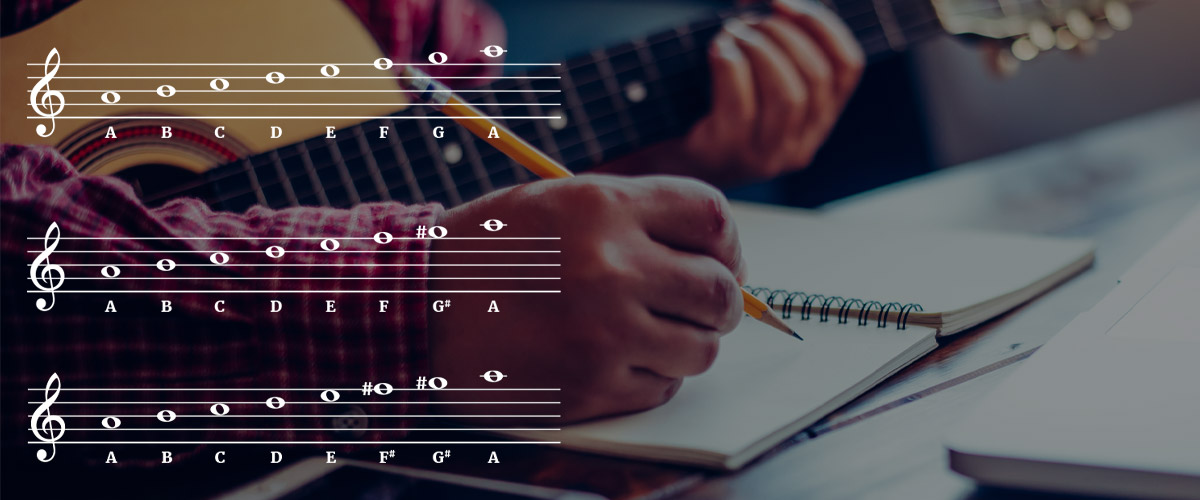

Below is an example of both an A Major scale and an A minor scale for comparison.

A Major Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# |

A minor Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

While we can learn the difference between major and minor scales (along with major and minor pentatonic and blues scales for example) based on using the Major scale as a reference (referred to as the master scale for this very reason) we can also assemble Major and minor scales using a formula known as a step or scale pattern based on the Chromatic scale.

If you need a refresher on reading scale charts, click here.

Step/Scale Patterns

As previously discussed Diatonic scales are constructed using whole and half steps.

Whole and half steps are musical intervals used to describe the distance between two notes. This becomes easier to understand when looking at an example.

But first, we need to learn the simplest of all scales, the Chromatic scale, aka the musical alphabet, or building blocks of western music, as this is the scale that contains all the notes used in Western Music.

All chords and scales are derived from the Chromatic scale, the difference being the step pattern used to construct the scale. Let’s look at an example to clarify this further.

In the diagram below we have the Chromatic scale which includes all 12 notes used in music, along with the scale degree of each note included above. In the example below A is our tonic (starting note) but we could conceivably begin on any note, provided we retain the same order.

The Chromatic Scale

| Scale Degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Notes | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# |

Major scale pattern

Knowing the Chromatic scale and the Major scale step pattern we can build a major scale.

Major scales are built on the following step pattern: Whole, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Whole, Half. Often shortened to W, W, H, W, W, W, H

Using the chromatic scale above, starting on A, we move up a whole step skipping A# and landing on B. From B we move up a whole step again to C# (keep in mind there are no sharps or flats between B and C and E and F) and from there we move up a half step to D.

From D we move up a whole step to E, and then another whole step to F# and then another whole step to G# which is a half step below our tonic (starting note) of A.

This gives us the following collection of notes:

A Major Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# |

Minor Scale Step Pattern

The minor scale step pattern is W H W W H W W

So, again taking the Chromatic scale and starting on A we take a whole step to B and from there a half step to C. From C we move up a whole step to D and then another whole step to E, before taking another half step to F. From F we move up a whole step to G and then another whole step to our tonic note of A.

In this example, due to how the notes are assembled, the scale of A minor contains no sharps or flats as shown below.

A minor Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

Keep in mind, in both examples, we are starting from A but we could start from any of the 12 individual notes which would define the key of the scale based on the tonic (first note of the scale).

Major and Minor Keys

What are keys?

A key is a sequence of notes, defined by the starting note (tonic) and the subsequent intervals used between notes. This doesn’t mean you need to use all notes of a given scale or are limited to only including notes of the corresponding scale in a song, but in most cases the notes used as the foundation of a song will come from a specific scale or mode, giving us the key of the song.

If you have spent any time learning music, you have probably already heard that songs in a minor key tend to sound sad while songs in major keys sound bright and happy.

This is certainly true in many cases. Take the classic ‘Sweet Dreams’ by the Eurhythmics, which is written in a minor key (C# minor) resulting in a brooding, melancholy sound. While ‘Don’t Worry, Be Happy’ by Bobby McFerrin is in a major key (C Major).

This isn’t necessarily always the case, there are exceptions. For example, the song ‘Happy’ by Pharrel Williams, is in the key of F minor, but this is more an exception than the rule. To put it in even simpler terms, Popular music often utilizes major keys while hard rock and metal are often minor, not always but often.

But what actually makes a minor scale and subsequently key sound darker than the more joyful sounding major key. The key (pardon the pun) are the intervals between notes or scale degrees.

For example, the interval between the tonic (starting note) and the important 3rd note of the major scale is a Major interval, known as the Major third (M3) which is four notes of the Chromatic scale apart). It’s generally accepted that this interval sounds brighter and more cheerful than the minor third (m3) which is the minor interval between the 1st and 3rd notes of the minor scale (3 notes of the chromatic scale).

This is certainly the case with chords and chord progressions.

For example, an A Major triad takes the 1st (root), 3rd (Major third), and 5th (perfect 5th) intervals from the major scale. Minor triads on the other hand also take the root, 3rd, and 5th notes of the corresponding scale but based on the minor scale this gives us a root, minor third, and perfect fifth. They may be only one note apart, but that minor third is what gives the chord its darker more menacing sound.

But why do our ears interpret this interval in that way?

For the most part, it’s part subjective and part contextual. It’s also too simplistic to simply label music as happy or sad sounding. Music is sophisticated, drawing a wide range of emotions from the listener.

But, perhaps the best explanation simply is over many years our sense of music has developed in this way to interpret minor intervals, scales, and chords as dark sounding while major musical components tend to sound brighter and more hopeful.

Take the example of ‘Happy Birthday’ a very bright sounding, yet simple song written in a major key, even featuring the words ‘happy’.

On the other hand the song ‘Black’ by Pearl Jam is written in E minor and the words and general mood of the song are very dark. Musicians use these musical components like a builder might use construction tools to create a distinct mood. It is no wonder a song with the title ‘Black’ that is written in E minor and features lyrics such as:

And now my bitter hands

Chafe beneath the clouds

Of what was everything

Oh the pictures have

All been washed in black

Tattooed everything

Conveys a sense of sadness to us.

Summary

While there are exceptions typically a song in a minor key, utilizing a minor scale will convey a sense of sadness or mystery while a song in a major key will sound less emotionally complex and convey happiness. Considering, in most cases, the only difference is the 3rd, 6th and 7th notes of the keys corresponding scale we can clearly see how powerful these subtle differences in music can be.